At the end of Chapter 5, the authors

use Pittsburghese as an example for linguistic identity. In a large paragraph,

they list several words and pronunciations that are associated with people who

live in Pittsburgh. This list includes the usual terms we hear: nebby, slippy, yinz.

After all that, however, we learn that outside of possibly the pronunciation of

“dahntahn” and the use of “gumband,” “none of these items is unique to Pittsburgh”;

instead, the idea of Pittsburghese is more about identity and the “people’s

pride in being residents of Pittsburgh” (154). This surprised me (although it

probably shouldn’t have). I didn’t realize that almost all of these linguistic

differences were not unique to Pittsburgh, and that the idea of having a “Pittsburghese”

was about the sense of having a “linguistic homeland.”

This all reminded me of the

linguistic biography I did about the different languages in China. My aunt

explained to me that small and distinct linguistic communities are what make someone

feel connected and part of a group. The idea of having an insider language that

only a certain group understands is not only useful, but unifying. She

mentioned that Mandarin, although it is the national language and gives people

a common ground, does not unite the Chinese people in the same way that local

languages do. This feeling of “groupyness,” found in smaller communities, is

strong. Perhaps the idea of identity related to Pittsburghese is similar in the

way it unites the people who live there and speak accordingly. But what’s the difference?

Does the person in China, who speaks several distinct languages, have a deeper

connection with those who are from the insider language than people who have only

a dialectal difference? Is there something to be said for the ability to move

in-and-out of multiple languages rather than switching between dialects? Also,

do dialects lead to distinct languages if groups of people are separated for

enough time?

Other

questions I had from this chapter…

- - Are

there any big differences in grammar across the linguistic regions of the US?

Our book talks about small differences that apply to just one phrase, but are

there overarching and applicable grammar rules that are distinct to a region?

- - The

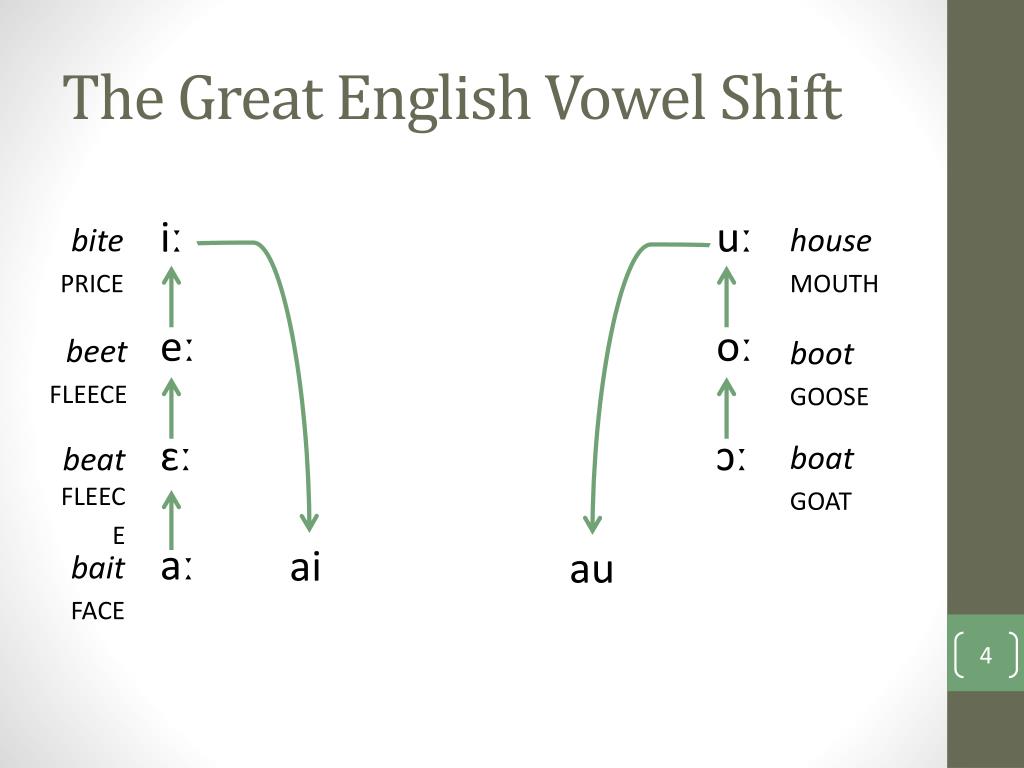

different vowel shifts are cool (pgs. 137-140)! Am I thinking correctly in

imagining them to become like the GVS we learned about in Intro. to

Linguistics? Will the vowels move enough to be completely new words so that the

dialects are extremely different in each region (so different that they cannot

be understood by outsiders)?

I find the idea of a "linguistic homeland" to be super interesting! I think you can look at internet language in a similar way to the Pittsburghese phenomenon. Especially in terms of generations, I feel like young people have truly adapted language online to reflect the new realities of communication. While some of the terms might now be used by the older generation (I know my mom uses lol for example), young people in my experience seem to cling to online terminology as an expression of our particular age group. The internet is the laboratory of the young where we have manipulated language to serve our new purposes. Pittsburgh residents have a pride in how they speak and it seems to me that young people online have a similar connection to online lingo. The internet is the forum upon which our generation has been able to express themselves differently than the way our parents were socialized.

ReplyDeleteIn particular, I think if one looks at online culture on sites such as Tumblr -- you could find examples of a type of "linguistic homeland". So-called "fandoms" have a variety of their own terms and ways of speaking that they use to identify themselves with one group over another. While it might be a stretch to refer to this as an insider language, I think the general concept still relates.

I hope my ramblings made some kind of sense, I am just fascinated with how language has adapted to fit the online environment.

Excellent observations, Kaylar. Language is truly a badge of social identity...

DeleteThis is a really cool idea! I agree that there is a kind of online culture that connects people with one another. And although this seems to be embraced by young people mostly, do you think that will change? As we become the older people (and technology changes), will we continue to keep our own "online language" that we had before? Will this language be known as something characteristic of older people then? Or will it change (and we'll follow)?

DeletePeople like feeling part of a group, and connecting to others. It's the same reason almost every culture has some kind of religion; not only can it be used to dissuade fear or explain the world, it brings people together with something they can all understand and relate to each other. It's also why old stories, religious or not, (The Odyssey, The Illiad, The Epic of Gilgamesh, Rapunzel, Cinderella), stay alive for so long in a culture; it's a way to bring people together with a unified cultural heritage.

ReplyDeleteYes, I agree we desire to belong in one way or another. It's a basic need - which I think is the reason all of this social distancing is so difficult to do.

DeleteI never fully contemplated the practical importance and significance of dialect until I came to college. I was born and raised in the same area my whole life, and many of the people I came into contact with had come from these same circumstances. Hence, we all spoke about the same way and used the same general range of vocabulary. However, once I got to college, dinnertime arguments about word usage became frequent. Big contenders were "sur-up" or "sear-up" (syrup), "cray-yon" or "cran" (crayon),"vuh-nill-uh" or "vuh-nell-uh" (vanilla), etc. These arguments often escalated to great intensity. Our ways of speaking informed our identities, and our identities informed our ideas of "correctness." How we each pronounced words was what we each insisted was the "right" way, and none of us were willing to budge on this.

ReplyDeleteI did notice growing up that my mom's family in New York had an accent, while they insisted to our family that we had one. I remember my siblings and I always poking fun at my mom for pronouncing certain things different, most notoriously for saying "league" as "lig." It is interesting because my friends from Northern PA (including Mr. Nicholas Allis of our ship) speak in a kind of accent that reminds me of my mom's family, Nic's accent being the strongest.

This brings me to your question about grammatical differences. My mom, for her own part, always cracked down on my siblings and me for saying that something "needs washed." We were always met with a swift and stern, "You mean, needs TO BE washed." After reading this chapter, I learned that this grammatical structure is part of the Pittsburghese dialect. My dad grew up primarily in the Pittsburgh area, so he was the culprit behind this bane to my mother's existence. My parents had contrasting linguistic identities, and my mom seemed to be determined that we inherit hers. Despite her best efforts, we assumed the speech patterns of those we were most often around. I guess you could say that the Western PA dialect developing within the majority of my family created a kind of "groupyness," from which my poor dear mother was the outsider (and butt of a few jokes, oops). However, I don't think it was to the point that us groupies had a deeper connection from which our mom was exempt.

Oh boy, one thing I just remembered. The crayon-cran issue was The Great Divide of my household growing up! My dad was a "crayon" man and my mom a "cran" girl. For whatever reason, this dialectal difference was scattered inconsistently through us kids. My mom, sister, and little brother were the "cran" side, while my dad and I were the "crayon" people. My older brother was the poor, confused middle man. He had fallen victim to the "cran" trend, yet he tried to train himself to say "crayon." Clearly, he had grasped that this was the superior pronunciation.

That's a lovely little linguistic memoir, Kate.

DeleteIt's really cool to hear some personal examples! I also get into more language "arguments" in college. :)

DeleteThe things you said about your mom - especially about something needing "TO BE washed" reminds me of my own family. I grew up with constant corrections about saying "yes" instead of "yeah" (something I never corrected), "may I" instead of "can I," pronouncing the word "often" without the sound of the 't,' and other things like these. I truly believed there was a "right" way to say words; I thought that you could learn this by studying sufficiently, that the correct way was always more logical. I learned pretty soon that this was not the case. However, there is still this idea, as you mention, of a "superior pronunciation," and I wonder why it's so important to people.

After reading chapter 5, I really understood the notion of having a sense of “linguistic homeland”. Being from the Pittsburgh area, I recognized that the variation in dialect brought people together. It created pride for the community and makes an area feel somewhat special or unique. People enjoy having the same values and bond over similarities. This can relate to all other dialects spoken around the world. They are attracted to what they ate familiar with and connect with the people who understand. It’s s communities niche.

ReplyDeleteYou make a really good point about how we are attracted to what we are familiar with. I think that this extends even farther than language - it's cool to think about!

DeleteIt is impressive how each locality has its own dialects, accents and words.during the time i was in clarion, i heard many of them, especilly yinz, not in its natural context, but i heard many people saying that word was very distinctive from Pittsburgh. I absolutely agree with the following statement : "My aunt explained to me that small and distinct linguistic communities are what make someone feel connected and part of a group". I experienced that when i first got to the USA, when i met a girl from Argentina in a Basquetball game. Usually Chilean and Argentinean do not get on very well, but in an English speaking country , i identified myself with her, since both of us were latinas and spoke the same language, and although i dont have problems expessing myself in english, i felt safe next to her, because she was form a very similar culture. There is anothe time in which i was staying in Queens. I was waiting for the bus, and there was a man next to me , talking by the phone, and he said " Uta'que mala" an expression only used in chilean Spanish meanin " oh, that's sad" or " that's a pitty". Again, I was very happy to see another Chilean in this totally new country for me, and the first thing I thought was " un chileno!" ( another chilean!). It is incredible how this idea of identity and sense of belonging is extremely connected with our language!

ReplyDeleteSweet! It's really cool to hear your stories of how this happened to you in the US! It's interesting how you bring up the idea of safety. I suppose sharing a language (in the midst of another) also helps people feel safe and grounded around each other. That makes so much sense!

DeleteVery nice post, Alice, and it brought out some excellent commentary. You raised some interesting issues which I'll respond to in a post of my own...

ReplyDelete