Tuesday, March 31, 2020

Example of a Multi-Purpose Survey

In Monday's Zoom, we talked about updating a survey, the Western Pennsylvania Local Speech Survey, I did in this class two years ago with new questions. Here's a heatmap we were able to generate from that survey, looking at the geographical distribution of the Pittsburghese word jumbo (for 'balogna'):

Here is a link to the questionnaire for that survey:

Anyway, look it over and try to think of new questions we might want to explore this time around. Post your suggestions in the comment section...

Monday, March 30, 2020

applying the power/connection grid outside of family dynamics

So unsurprisingly enough I decided to focus a lot more of my blog post to the two out of text book articles as they were more interesting and I felt like had a lot more to offer than the book this week. I also chose to take a closer look at Gender and Family interaction as opposed to vowels and nail-polish as I had already been exposed to that piece last year with my previous anthropology class. Overall I find gender to be one of the most interesting topics to talk about as it seems to be a topic that many people are very guarded about, for good reason as no one wants to offend someone else, but gender is one of the topics that has the greatest impact on language development as well as how languages evolve and change over time. Anyway now onto the Gender and Family article. I overall found the article to be full of some very interesting topics but one of the largest ones that stood out to me was the power/connection grid. I find it interesting as it effects the dynamics of each individual family as a whole but also can always be changing and fluid as families can easily become closer or more distant to one another and in some cases can also have their power become more equal or hierarchical. I find this interesting and actually thought of what other circumstances other than just family could this grid be applied to. I think it has a reach much further beyond just looking at family dynamics and one of the most obvious to me was in the classroom. I feel like this translates very easily as in some classroom the teacher has total control and are very authoritarian in their control not letting students give much feedback which in turn also makes them kinda distant with one another and the teacher as they do not get to have that connection that allows them to feel included into discussion with one another. On the flip side there are classes like ours I feel like that allows us to easily be equal with one another. I feel like there are a number of different reasons for this but I think it makes us a much more connected classroom than the ones where the teacher lectures and the students only take notes. In our classroom, I never feel like I am being forced to talk or stay quiet and instead it is only up to each person's individual choice if he/she wants to speak. this I feel like also makes it a very equal space for everyone. In my opinion, having been in both styles of classrooms, I feel like this style where we are all equal for the most part and are able to freely bounce ideas off of one another and are not directly limited by the idea where the teacher lectures and the students only take notes and do not get a chance to drive the conversation; to be a style where ideas are given a chance to be shared more readily and can actually be changed as well as challenged in a way that really fosters intellectual thinking and discussion that is lacking in the other style.

Sunday, March 29, 2020

A Linguistic Cry for Help

For my blog post this week, I decided to look into Lapgaliski, which I had learned about when I interviewed my friend Marija for the linguistic biography. Before we get down to business, let me just establish that I, apparently, have been spelling it wrong this whole time. It is, in truth, spelled Latgaliski. Oops. Also, it appears to also be referred to under the alias of Latgalian. This language thing is a whole new level of mess.

From what Marija told me, there is debate in Latvia over whether it is simply a dialect of the Latvian language, or whether it qualifies as its own distinct language. I was curious to see where this confusion lies, so I did some digging.

It is said to be used primarily in an eastern region of Latvia called Latgale, although there is a small fraction of speakers also in Russia, Germany, Canada, and the United States. There are 150,000 - 200,000 speakers of the language; compare that to 1.5 million Latvian speakers and 265 million Russian speakers. Most Latgalian speakers are trilingual in Latgalian, Latvian, and Russian, and although it is not acknowledged legally, it is optionally taught at some preschools and is used in some primary and secondary schools for studies in local history. It additionally has a written component, leading to the establishment of its own canon of literature and folklore. Its cultural contributions expand also to theatre, music, newspapers, and radio broadcasts. More simply, Latgalian exists as the primary mode of communication within the Latgale region and within families, such that there are some elders who have practical familiarity with Latgalian but not its parent language, Latvian.

So, based on these new bits of information, do you think Latgalian is classified better as a dialect or a minor language? What qualifications exist to decide what makes a form of communication its own language? Let me know what you think! :)

Latgale, the land of beautiful scenery and confusingly spelled words.

Source

The Chilean Way: a basic guide to speak Chileno

During the time I was in the USA, many people asked me to speak a little bit of Spanish,whether it was out of curiosity or because they spoke Spanish too.This situation made me feel a bit uncomfortable, mainly because I had to speak a neutral Spanish in order to be understood.I knew that if I talked to them with my natural Chilean accent, they would look at me perplexed.

Somehow, I thought I was being unfaithful to my own identity. Therefore in an attempt to keep my chilenity, I stated to explain some modisms and features of my language (what I like to call Chilean Spanish) to the people a talked to.

First of all, we tend to OMIT some letters at the begining and at the end of a word. For instance in the following sentence: Estoy enamorado ( meaning " I'm in love"), we eliminate 'es' in estoy and the 'd' in enamorado, changing to: ´Toy enamorao. This patern is repeated in all words ended in "do". Sometimes, especially in a semi-formal context ,s, turns into a very soft derivation of h: E'htoy enamorao/ E'htamoh cansadoh ( instead of estamos cansados, meaning "we are tired").

Another distinctive feature is to place the word "la" (the) before a name when both speakers know the person. This is often used in informal and semi-formal conversations:

Eg -¿Quien te dio ese libro? ( Who gave you that book?)

-La Sthephanie me lo dio ( Sthephanie did)

The complexity of Chilean Spanish not only is due to these particular characteristics and grammatical deviations, but also for some words and expressions which literal translation does not have any sense without the context.The following link shows a useful article with some of the most used Chilean slangs.

Which of them caught your attention the most? Do you think you would be able to survive in the Chilean jungle?

Friday, March 27, 2020

Linguistic "Groupyness"

At the end of Chapter 5, the authors

use Pittsburghese as an example for linguistic identity. In a large paragraph,

they list several words and pronunciations that are associated with people who

live in Pittsburgh. This list includes the usual terms we hear: nebby, slippy, yinz.

After all that, however, we learn that outside of possibly the pronunciation of

“dahntahn” and the use of “gumband,” “none of these items is unique to Pittsburgh”;

instead, the idea of Pittsburghese is more about identity and the “people’s

pride in being residents of Pittsburgh” (154). This surprised me (although it

probably shouldn’t have). I didn’t realize that almost all of these linguistic

differences were not unique to Pittsburgh, and that the idea of having a “Pittsburghese”

was about the sense of having a “linguistic homeland.”

This all reminded me of the

linguistic biography I did about the different languages in China. My aunt

explained to me that small and distinct linguistic communities are what make someone

feel connected and part of a group. The idea of having an insider language that

only a certain group understands is not only useful, but unifying. She

mentioned that Mandarin, although it is the national language and gives people

a common ground, does not unite the Chinese people in the same way that local

languages do. This feeling of “groupyness,” found in smaller communities, is

strong. Perhaps the idea of identity related to Pittsburghese is similar in the

way it unites the people who live there and speak accordingly. But what’s the difference?

Does the person in China, who speaks several distinct languages, have a deeper

connection with those who are from the insider language than people who have only

a dialectal difference? Is there something to be said for the ability to move

in-and-out of multiple languages rather than switching between dialects? Also,

do dialects lead to distinct languages if groups of people are separated for

enough time?

Other

questions I had from this chapter…

- - Are

there any big differences in grammar across the linguistic regions of the US?

Our book talks about small differences that apply to just one phrase, but are

there overarching and applicable grammar rules that are distinct to a region?

- - The

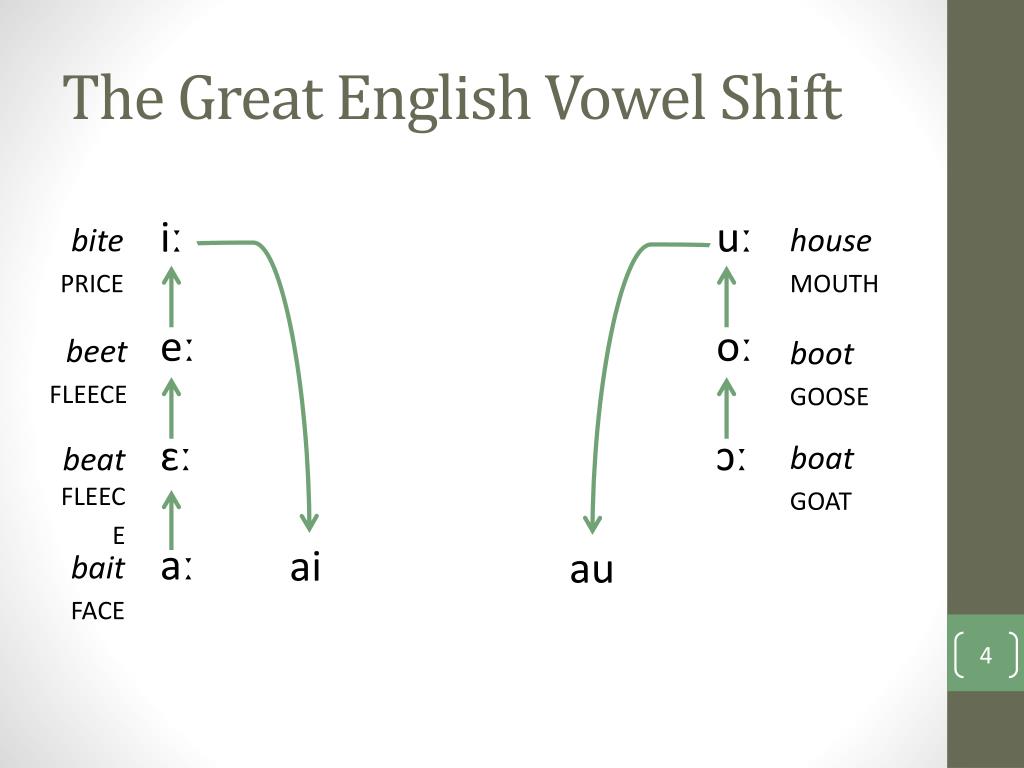

different vowel shifts are cool (pgs. 137-140)! Am I thinking correctly in

imagining them to become like the GVS we learned about in Intro. to

Linguistics? Will the vowels move enough to be completely new words so that the

dialects are extremely different in each region (so different that they cannot

be understood by outsiders)?

Wednesday, March 25, 2020

Everything's Bigger in Texas...Unless You're Looking at a DARE Map.

What sparked my interest about Chapter 5 actually happened quite early in the chapter. In section 5.2 on page 128 while talking about mapping regional variants it mentioned how some of the earlier computerized cartographic maps, including DARE maps, displayed states based on population density rather than geographical area. Because of this, a state like Texas which is geographically large, appeared smaller than New York. Personally, I would have never thought that this could happen. I've always assumed that every state had a fairly even amount of regional variants, and if anything, I thought that bigger states had more than smaller states. In retrospect however, it does make sense, as areas with higher population density act as melting pots where people are exposed to so many other cultures that they eventually lose their linguistic purity. So, while it does make sense, I am still hung up on the fact that it's Texas we're talking about. As Texas is on the Mexican border I would have thought there would have been a similar amount of regional variants compared to somewhere like New York. So, as a question to the rest of the class, do you think this is because Texas is only dealing with two main cultural groups while New York has multiple cultural groups within it (Even though each group individually within New York likely isn't as big as the Hispanic/Mexican culture in Texas)?

What sparked my interest about Chapter 5 actually happened quite early in the chapter. In section 5.2 on page 128 while talking about mapping regional variants it mentioned how some of the earlier computerized cartographic maps, including DARE maps, displayed states based on population density rather than geographical area. Because of this, a state like Texas which is geographically large, appeared smaller than New York. Personally, I would have never thought that this could happen. I've always assumed that every state had a fairly even amount of regional variants, and if anything, I thought that bigger states had more than smaller states. In retrospect however, it does make sense, as areas with higher population density act as melting pots where people are exposed to so many other cultures that they eventually lose their linguistic purity. So, while it does make sense, I am still hung up on the fact that it's Texas we're talking about. As Texas is on the Mexican border I would have thought there would have been a similar amount of regional variants compared to somewhere like New York. So, as a question to the rest of the class, do you think this is because Texas is only dealing with two main cultural groups while New York has multiple cultural groups within it (Even though each group individually within New York likely isn't as big as the Hispanic/Mexican culture in Texas)?[P.S. it should be noted that everything I stated is pure speculation, I am not educated on Texas demographics or New York demographics...]

Tuesday, March 24, 2020

Linguistic Holes

So, one thing that caught my eye whilst reading chapter five, looking at dialect maps, and reflecting on conversations from English 282 and this class was the make up of dialectal boundaries. On page 130 of the textbook (I was able to find the image on Google and attach it above), there is a map depicting the spread of the use of the word pail. I was really interested in the fact that you could pretty much draw a line across the center of Pennsylvania and separate the pail people from the bucket people. As I kept looking at the above map, I noticed the lingering parts of PA that use the pail. My theory is that these are areas that saw overflow from West Virginia and New Jersey because the flow into Western PA clearly has roots in WV. Likewise with Eastern PA having overflow from NJ. However, as we look at other states in this map, we can see somewhat random breaks in the dialectal continuation. In West Virginia, we can see the continuation in the northeast, but then there is a break that picks up again towards the middle of the state, another break, then it picks up towards the southern border of the state. This continuation on the southern border seems to stem from a chain that stretches from most of Georgia, South Carolina, and some of North Carolina.

However, like I said before, there are several spots in Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina where bucket is used over pail, so the question(s) I pose to all of you is: how or why do these gaps form? Do you think part of their formation comes from the movement of people to certain areas and not others? Why do you suppose there are non-concentrated areas surrounded by concentrated areas in the southern states in the above map?

(I apologize for the quality of the image, but that's the best I could do. A clearer, larger image can be found on page 130 of the textbook.)

Sunday, March 22, 2020

Good Will Shakespeare

Whenever one mentions the name “William Shakespeare,” many different thoughts flood throughout many different minds. Some roll their eyes; some openly praise him; some utter the word “overrated”; some do not care. No matter who you are, though, or what you think about his work, one cannot deny his brilliance.

It is obvious that Shakespeare changed the game for literature, theatre, and writing, but what most people do not realize is how much his work impacted the English language as a whole. True, there are people who read Romeo and Juliet and/or Julius Caesar in high school that do not care about his achievements, and might even find them overvalued; however, no one can escape his contributions.

Why is this?

Well, Shakespeare had knowledge of seven different languages, and had an estimated vocabulary of about 24,000 words; a truly staggering amount. This background allowed for him to invent new words for the English language-- over 1,700 to be exact-- and also to flesh out our language in more ways than one. In many ways, these words are his most underrated works. Below are some of the most popular (I copied and pasted the word list from William Shakespeare: His Influence in the English Language):

Well, Shakespeare had knowledge of seven different languages, and had an estimated vocabulary of about 24,000 words; a truly staggering amount. This background allowed for him to invent new words for the English language-- over 1,700 to be exact-- and also to flesh out our language in more ways than one. In many ways, these words are his most underrated works. Below are some of the most popular (I copied and pasted the word list from William Shakespeare: His Influence in the English Language):

Eyeball, moonbeam (A Midsummer Night’s Dream)Which are your favorites?

Puking (As You Like It)

Obscene, new-fangled (Love’s Labour’s Lost)

Cold-blooded, savagery (King John)

Hot blooded, epileptic (King Lear)

Addiction (Othello)

Arch-villain (Timon of Athens)

Assassination, unreal (Macbeth)

Bedazzled, pedant (The Taming of the Shrew)

Belongings (Measure for Measure)

Dishearten, swagger, dawn (Henry V)

Eventful, marketable (As You Like It)

Fashionable (Troilus and Cressida)

Inaudible (All’s Well That Ends Well)

Ladybird, uncomfortable (Romeo and Juliet)

Manager, mimic (A Midsummer Night’s Dream)

Pageantry (Pericles)

Scuffle (Antony and Cleopatra)

Bloodstained (Titus Andronicus)

Negotiate (Much Ado About Nothing)

Outbreak (Hamlet)

Jaded, torture (King Henry VI)

Grovel (Henry IV)

Gnarled (Measure for Measure)

Labels:

English,

Nate,

Shakespeare,

vocabulary,

words

Friday, March 20, 2020

Ideas to Be Thinking About

So what are we going to do with ourselves the rest of the semester, besides read some stuff and talk about it? I have always, with this class, made a point of doing a class project—interviewing people (check: did that), collecting data about some aspect of dialect, testing a theory—and I am loath to let that go, even in our diminished sequesterment.*

At our first Zoom session (which turned out to be fun, I thought), we talked about a few ideas for potential surveys (online, obviously, given the present circumstances). As I recall, these were as follows:

Personally, I think they all sound like fantastic research avenues. So why don't yinz-all think about them and decide which ones you think sound interesting to you, that we might like to work on as a class in the time we have left. Maybe we could even break into groups to tackle more than one of them...

Thoughts, anyone? (You can blog on these ideas yourselves, as well...)

* New word. You saw it here first, folks!

At our first Zoom session (which turned out to be fun, I thought), we talked about a few ideas for potential surveys (online, obviously, given the present circumstances). As I recall, these were as follows:

Pittsburghese — There are reports that Pittsburghese is experiencing considerable dialect swamping, and is beginning to fade in the speech of younger generations. Conversely, to what extent are incoming outsiders picking up aspects of Pittsburghese in their own speech as tokens of acculturation? Can we figure out a way to explore these questions?

Dialect & Gender — There are all kinds of ways in which our gender influences our speech. Reading up and focusing on some of those patterns, can we devise some kind of survey that would show this in action?

Language of Social Media — There is a lot of research on this of late, but I don't know what's in it. People would have to read into it and figure out how to do something with it. Could be very interesting...

Loss of Rural Vocabulary — A whole lexicon of older mostly rural expressions of Western Pennsylvania seem to be disappearing. The last time I taught this class we looked into some of this; there is a lot more to explore...

Personally, I think they all sound like fantastic research avenues. So why don't yinz-all think about them and decide which ones you think sound interesting to you, that we might like to work on as a class in the time we have left. Maybe we could even break into groups to tackle more than one of them...

Thoughts, anyone? (You can blog on these ideas yourselves, as well...)

Wednesday, March 18, 2020

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)